A Professor and Apostle Correspond: Eugene England and Bruce R. McConkie on the Nature of God

By Rebecca EnglandWe must truly listen to each other, respecting our essential brotherhood and the courage of those who try to speak, however they may differ from us in professional standing or religious belief or moral vision . . . and then our dialogue can serve both in truth and charity.

—Eugene England, 1966

It is my province to teach to the Church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo what I say or to remain silent.

—Bruce R. McConkie, 1981

One of the most troubled times of my life came about when I failed to make the distinction between Brother and Brethren.

—Eugene England, 1993

_____________________

IN LATE MAY 1981, Professor Eugene England returned to the BYU London Centre after spending the previous month directing Study Abroad students traveling on the European continent as part of their six-month coursework. He was still unsettled by the shocking experience of witnessing just days earlier the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II’s life in St. Peter’s Square. These were the circumstances during which he found in his stack of unopened mail a ten-page letter from Elder Bruce R. McConkie that began: “This may well be the most important letter you have or will receive.” Dated19 February 1981, the letter was Elder McConkie’s response to a letter and essay England had sent to the apostle on 1 September 1980.

Three decades later, McConkie’s letter to England is closely associated with these two influential Mormon intellectuals. When someone enters a Google search for either “Eugene England” or “Bruce R. McConkie,” links to websites containing the full text of McConkie’s notorious letter appear at or near the top of the list. According to historian Claudia Bushman, “a microcosm of the diverging styles” of faithful Church intellectuals can be seen in this “celebrated showdown between England, a provocative thinker . . . and McConkie, a lawyer and doctrinaire General Authority.” She believes the “McConkie-England disagreement revealed the division between theological conservatives and liberals within the believing camp and, in a larger sense, the tension between authoritarian control versus free expression.”1

Three decades later, McConkie’s letter to England is closely associated with these two influential Mormon intellectuals. When someone enters a Google search for either “Eugene England” or “Bruce R. McConkie,” links to websites containing the full text of McConkie’s notorious letter appear at or near the top of the list. According to historian Claudia Bushman, “a microcosm of the diverging styles” of faithful Church intellectuals can be seen in this “celebrated showdown between England, a provocative thinker . . . and McConkie, a lawyer and doctrinaire General Authority.” She believes the “McConkie-England disagreement revealed the division between theological conservatives and liberals within the believing camp and, in a larger sense, the tension between authoritarian control versus free expression.”1

Because copies were widely circulated, McConkie’s 1981 letter has impacted many people beyond just England, including his family, friends, and many Latter-day Saints who felt that Elder McConkie’s authoritarian and threatening tone was unbefitting an apostle of Jesus Christ. Others saw the McConkie letter as an expression of one of the Lord’s anointed apostles acting fully in harmony with his calling, which includes correcting—even with sharpness—ideas that might be harmful to faith. A prolific personal essayist, England never spoke or wrote publicly about the controversy except for a few paragraphs in his 1993 essay, “On Spectral Evidence.” However, documents found in England’s papers help reconstruct and give context to this remarkable exchange between a Latter-day Saint professor and apostle.

ON 13 SEPTEMBER 1979, Professor England was scheduled to speak to BYU honors students. His talk—“The Lord’s University?”—would address the Latter-day Saint ideal of continuing, life-long education through a review of, among other examples, the Mormon doctrine of eternal progression in knowledge. It would also include an invitation for the audience to respond to Joseph Smith’s optimistic view of unlimited human potential in relation to divinity as expressed in his last major sermon, the King Follett Discourse. The evening before the scheduled lecture, England received a phone call at home from Joseph Fielding McConkie, a BYU religion professor. Professor McConkie had read an earlier version of “The Lord’s University?” and told England he thought his father, Elder Bruce R. McConkie, would strongly disapprove of its content. After a lengthy conversation, England invited Professor McConkie to the lecture so he could share with the audience what he felt his father’s objections might be. After hanging up the phone, England discussed the conversation with his wife, Charlotte, who expressed her concern that the interaction could become negative and advised against inviting McConkie to participate. England, however, thought it would be beneficial for students to see the respectful exchange by faculty members of differing opinions.2

After giving his lecture, England invited Joseph McConkie to respond. In his response, McConkie stated that his father, Elder McConkie, and grandfather Joseph Fielding Smith, taught of a god that is not progressing and whose perfection is absolute. “Though I accord a man the privilege of worshipping what he may, there is a line—a boundary—a point at which he and his views are no longer welcome.” Joseph concluded: “I do not see the salvation of BYU in the abandonment of absolutes, and with the prophets whose blood flows in my veins, I refuse to worship at the shrine of an ignorant God.”3 As audience members sat stunned at the combative and superior tone of Professor McConkie’s remarks, England attempted to ease the tension in the crowded lecture hall and restore collegiality by expressing his appreciation for Brother McConkie’s response and acknowledging the educational value for students to hear such an open and honest exchange of ideas.

After giving his lecture, England invited Joseph McConkie to respond. In his response, McConkie stated that his father, Elder McConkie, and grandfather Joseph Fielding Smith, taught of a god that is not progressing and whose perfection is absolute. “Though I accord a man the privilege of worshipping what he may, there is a line—a boundary—a point at which he and his views are no longer welcome.” Joseph concluded: “I do not see the salvation of BYU in the abandonment of absolutes, and with the prophets whose blood flows in my veins, I refuse to worship at the shrine of an ignorant God.”3 As audience members sat stunned at the combative and superior tone of Professor McConkie’s remarks, England attempted to ease the tension in the crowded lecture hall and restore collegiality by expressing his appreciation for Brother McConkie’s response and acknowledging the educational value for students to hear such an open and honest exchange of ideas.

This Eugene England and Joseph McConkie exchange might have remained a much-discussed disagreement between BYU professors that would fade with memory. However, nine months later, on 1 June 1980, Elder Bruce R. McConkie delivered at a BYU Devotional, a lecture entitled “The Seven Deadly Heresies.” The primary “heresy” Elder McConkie warned against was the belief that “God is progressing in knowledge and is learning new truth. This is false, utterly, totally, and completely.” He further stated that we cannot be saved unless we believe that the “truth as revealed to and taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith is that God is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent.” McConkie belittled those who think otherwise as having “the intellect of an ant and the understanding of a clod of miry clay in a primordial swamp.”4

McConkie’s talk immediately generated heated discussion among faculty and students. In Lengthen Your Stride, a biography of Spencer W. Kimball’s Presidency years, Edward Kimball refers to this incident:

President Kimball was not doctrinaire, and he felt a need to interfere in doctrinal matters only when he saw strong statements of personal opinion as being divisive. Elder McConkie’s talk at BYU on “The Seven Deadly Heresies” implied he had authority to define heresy. . . . President Kimball responded to the uproar [caused by the devotional] by calling Elder McConkie in to discuss the talk. As a consequence, Elder McConkie revised the talk for publication so as to clarify that he was stating personal views and not official Church doctrine.5

This was not the first or last time that Elder McConkie would be quietly corrected by a Church president for causing controversy and division. For generations, Latter-day Saints have cited Bruce R. McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine as an authoritative source of official Church doctrine. However, its unauthorized publication in 1958 met with strong disapproval and objections by President David O. McKay, the First Presidency, and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. At the direction of President McKay, an analysis of the book by two apostles noted its many doctrinal errors, offensive statements, and overly authoritative tone. President McKay directed that the book not be republished and that it be repudiated. Elder McConkie also was privately reprimanded by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve for his problematic publication.6 However, few students or faculty were aware that Church prophets and authorities ever disapproved of and required corrections of Elder McConkie’s spoken or written words. Many did not distinguish his opinion from official Church doctrine; others found McConkie’s statements contradicting other Church leaders confusing.

England considered McConkie’s “Seven Deadly Heresies” talk, along with other writings and sermons by Church leaders, and drafted a new paper, “The Perfection and Progression of God: Two Spheres of Existence and Two Modes of Discourse.” Then, on 1 September 1980, England typed a letter to McConkie on his home office Underwood manual typewriter. In taking this step to share his concerns privately with Elder McConkie, England hoped to avoid public controversy and find McConkie more open-minded in personal conversation than what was suggested by his public rhetoric. In his “Bruce R. McConkie” file, Eugene kept a copy of “All Are Alike unto God,” an address McConkie gave soon after the 1978 revelation on the priesthood, in which Elder McConkie admits to having misinterpreted the scriptures and statements of previous prophets: “Forget everything that I [and others] have said . . . contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding.”

During his life and career, England had personally known, sought counsel from, and received the support of a number of Church leaders whom he held in high regard. He and Charlotte had especially positive associations with Hugh B. Brown, Marion D. Hanks, Harold B. Lee, Spencer W. Kimball, and David B. Haight. Never having personally interacted with Elder McConkie, England begins his letter by expressing warmth and admiration for the apostle, especially his testimony of Jesus Christ: “I was especially moved by your witness and psalm of praise in last April conference.” After briefly recounting the disagreement with his son Joseph the previous year, he explains why he is writing now to the apostle:

After last fall’s lecture, I got a copy of your son’s response, studied it carefully, and decided that his strong feeling that I was out of harmony required that I rethink the whole matter. So I have, this past year, carefully and prayerfully gone back over all the pertinent sources I could find and have written the enclosed paper about my findings. . . . But I recognize that I could certainly be wrong, that I could be interpreting Joseph Smith and Brigham Young and others incorrectly, or that subsequent revelation has invalidated what they said. I accept the authority of the living prophets and not only want to be but assume I am fully in harmony with them, including, of course, with you. If not, I want to be put right.

It would be gracious of you to read my paper and give me some response if you feel there is need. If you have any question about my ability or good faith before you take the time to read my work, you could check with Elder Boyd K. Packer or Elder David B. Haight, both of whom know well my mind and spirit.

In January 1981, England began the aforementioned six-month assignment as Associate Director for BYU London Study Abroad, so he was out of the country when Elder McConkie eventually wrote a response. Before England had even received McConkie’s letter or knew of its existence, however, copies that had originated from the apostle’s office were already circulating on the BYU Provo campus.

After stating, “This may well be the most important letter you have or will receive,” McConkie acknowledges the receipt of England’s letter and the enclosed paper. He briefly summarizes the contents, states he does not participate in discussions of controversial subjects, but had eventually decided, partly out of respect for Eugene’s parents, to answer England’s letter. “I shall write in kindness and in plainness and perhaps with sharpness. I want you to know that I am extending to you the hand of fellowship though I hold over you at the same time, the scepter of judgment.”

Long passages of the letter consist of quotes from McConkie’s own speeches and state his opposition to the idea of a god who progresses and his fear that such a concept could lead to questions that undermine faith: “Will [God] one day learn something that will destroy the plan of salvation and turn man and the universe into uncreated nothingness?”

In his response, McConkie also makes several statements about Brigham Young that would eventually catch the attention of anti-Mormon groups, who regularly quote the letter. McConkie says that while Brigham Young was a prophet, he did not always speak as a prophet and sometimes “expressed views that are out of harmony with the gospel” [and] “erred in some of his statements on the nature and kind of being that God is. . . . What [Brigham Young] did is not a pattern for any of us. If we choose to believe and teach the false portions of his doctrines, we are making an election that will damn us.”

After directing England to cease speaking on the subject of the progression of God or sharing copies of his paper on the subject, McConkie emphatically states: “It is my province to teach to the Church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo what I say or to remain silent.”

McConkie then expresses his expectation that if England is “receptive and pliable,” he will “get the message.” He follows with a prayer for his well-being and an invitation to visit privately in his office if England so desired, but he then adds what is hard to interpret as anything other than a dig: “Perhaps I should tell you what one of the very astute and alert General Authorities said to me when I chanced to mention to him the subject of your letter to me. He said: ‘Oh dear, haven’t we rescued him enough times already.’”

The letter closes with an additional warning to England that his soul’s salvation depends on accepting the apostle’s counsel: “It is not too often in this day that any of us are told plainly and bluntly what ought to be. I am taking the liberty of so speaking to you at this time, and become thus a witness against you if you do not take the counsel.”

DISTRESSED UPON REALIZING that an apostle saw him as a nuisance and potential heretic, as well as that a sensitive, private letter had been made public, England soon wrote a letter to clear up misunderstandings and assure McConkie that he wrote sincerely asking for McConkie’s judgment of his efforts to build faith in his students by harmonizing apparent differences in prophetic statements on the nature of God, and that he would “obey his directions exactly.” Most of England’s friends and family were unaware of his struggle to respond with integrity to McConkie’s letter of reprimand.

Upon his return to Utah from London, other priorities emerged, allowing the heartache caused by these exchanges with the apostle to fade into the background. England became fully engaged in other activities, such as founding the non-profit charity Food for Poland, continuing to develop and teach the BYU freshman honors colloquium, teaching Shakespeare and American and Mormon literature, writing scholarly and personal essays, assisting Charlotte in caring for her dying mother in their Provo home, and serving as bishop of a BYU young married students’ ward.

Shortly after the controversy over the letter began to subside, another incident occurred on the BYU campus that stirred up similar feelings about the way Elder McConkie would sometimes choose to exercise his right as an apostle to correct what he saw as false doctrine or practices that could potentially prove harmful to faith. The catalyst for this renewed stir was a 2 March 1982 televised speech in which McConkie publicly censured popular BYU religion professor George W. Pace (and a colleague of his son, Joseph F. McConkie) for teaching his views about the importance of developing a personal relationship with the Savior, Jesus Christ. Following this talk, McConkie again received private counsel and correction from President Spencer W. Kimball. In response to McConkie’s rebuke, Pace, a longtime friend and colleague of England’s since the 1960s when they had taught together at the Stanford University LDS Institute of Religion, publicly apologized and stopped teaching and writing about developing a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

England decided to engage Elder McConkie later that year, not over the Pace censure but because he had learned that the McConkie letter to him had been recently published by disaffected Mormons Jerald and Sandra Tanner, who had taken special interest in the apostle’s candid statements about President Brigham Young’s having at times taught false doctrine. In a short 29 October 1982 letter to McConkie, England reassures the apostle that he has secured the original letter McConkie sent to him and had never released a copy. “Perhaps you should know that I have learned recently that a copy of your letter was seen here at Brigham Young University just a few days after it was written, in early 1981 and long before I received the letter in England. It was understood that the copy had somehow originated in your office.” He also regrets the ripples of controversy surrounding their interchange “over what I have consistently intended and felt was an honest and faithful pursuit of truth and understanding. It is still not entirely clear what lessons I have learned, but I am sincerely trying. May the Lord continue to bless you in your powerful work as a special witness of Christ.”

AS HE HAD promised the apostle, England did not publicly teach his beliefs about God being both perfect and progressing until four years after Elder McConkie’s death. (In this way, he honored the apostle’s counsel: “It is my province to teach to the Church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo what I say or to remain silent.”) Feeling he was no longer bound to follow McConkie’s counsel of silence, England published “Perfection and Progression: Two Complementary Ways to Talk About God” in the 1989 summer issue of BYU Studies. The acceptance of this essay in BYU Studies is, itself, a recognition by editors faithful to the church that the two views of God co-exist within Mormon thought and are worth at least considering and attempting to reconcile.

In his 1993 essay “On Spectral Evidence,” England looks back on the controversy surrounding McConkie’s letter. In it, England begins to give shape to those “not entirely clear” lessons he was to have been learning from his interactions with Elder McConkie, wondering out loud if he may have violated his own integrity by so readily promising to be silent when faced with McConkie’s reprimand.

Certainly it is possible for an individual among the Brethren to ask me to do or believe something I simply could not, at least in good conscience. As Elder Boyd K. Packer explained in a devotional address at BYU in 1991, safety lies in the motto, “Follow the Brethren, not the Brother.”7

Using that idea as a springboard, England reflects on “one of the most troubled times of [his] life [when he] failed to make the distinction between Brother and Brethren” and reviews his intentions in contacting McConkie, along with his feelings of hurt and bewilderment at the apostle’s harsh response. He then reflects further on his promise of silence, his efforts to be obedient and open-hearted toward this general authority, his concerns about publicity, and his eventual decision to break his silence after McConkie’s death.

It was certainly not my prerogative to publicly challenge or oppose Elder McConkie’s ideas, especially while he was serving as an apostle. But neither did it any longer seem right for me to remain silent about what I understood to be an important and official teaching of the Restoration affecting the education of my students, so in 1989 I published an essay in Brigham Young University Studies, exploring as objectively as possible two complementary ways of talking about God—as perfect and as progressing.

Throughout the remainder of his life, England consistently taught what he saw as a unique Mormon theological teaching of a perfect and progressing God, but he always remained respectful of the diversity of opinion on the subject. Perhaps England’s most eloquent presentation of his views on the paradoxical nature of a being both perfect and progressing is found in one of his final essays, “The Weeping God of Mormonism.” There, England harmonizes a way of honoring Elder McConkie’s concern about people possibly losing faith if they were to believe in a Deity who was other than “omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent.” Commenting on differences between theological positions presented in the “Lectures on Faith,” an early doctrinal exploration, and Joseph Smith’s later views, England writes:

I think [Joseph Smith] eventually saw no inherent contradiction between the Lectures and his later understanding of God as having “all” knowledge and power, sufficient to provide us salvation in our sphere of existence (and thus being “infinite”), but also as one who is still learning and developing in relationship to higher spheres of existence (and thus “finite”). God is thus, as Joseph understood, redemptively sovereign, not absolute in every way, but absolutely able to save us.

INDIVIDUAL TEMPERAMENT RATHER than logical argument may ultimately cause one individual to believe in an unchanging God with absolute knowledge and limitless power and another to be drawn to a more personal God limited by natural laws and somehow progressing in knowledge. As noted earlier, Claudia Bushman suggests that in many ways Eugene England and Bruce R. McConkie represent the liberal and conservative strains of orthodox Mormon intellectuals. In his attempts to describe and continue this dialectic in Mormon theology, Eugene England valued and invited dialogue between different perspectives rather than rushing to settle debates about the nature of God. Confident in the reality and benevolence of God, England concludes his 1989 BYU Studies essay on the nature of God by embracing adventure and a degree of risk in an open universe without end. In contrast, Elder McConkie felt no reservations at claiming authority to define and declare gospel truth. His testimony was of God’s omniscience and omnipotence, and he unhesitatingly warned his audiences to adopt his views or risk straying into apostasy. One approach invites dialogue; the other silences dissent.

When questioned by his family, colleagues, and students about his thoughts and feelings surrounding Elder McConkie, England was consistently and remarkably sympathetic and respectful of the apostle. His children have no recollections of their father expressing bitterness toward Elder McConkie, or any other apostle. Immediately following the broadcast of the April 1985 General Conference in which Elder McConkie gave what turned out to be his final talk before his death thirteen days later, England commented on how moving he found Elder McConkie’s personal testimony of the Savior.

Online discussions reveal that curiosity about the England and McConkie exchange has not waned in the three decades since it took place, as it raises important questions about the rights and responsibilities of individuals as they relate to religious authority. Many individuals take sides, severely faulting either England or McConkie. Some assume England must have grievously erred to receive such a stern rebuke from an apostle; others find McConkie’s counsel harsh, heretical, arrogant, and even spiritually abusive.

What clearly emerges in the exchange, however, is that both England and McConkie saw themselves as defenders of the faith—loyal believers with profound testimonies of Jesus Christ and the restored gospel. As Latter-day Saint intellectuals obviously committed to their faith, England and McConkie were nevertheless near opposites in their temperaments and approaches to paradoxical positions. In this instance, the correspondents were concerned with the Latter-day Saint understanding of the nature of God. The differences between England and McConkie bring to mind the conflicts between Brigham Young and Orson Pratt recounted in Gary James Bergera’s Conflict in the Quorum,8 with England favoring Young’s position on a progressing God and McConkie siding with Orson Pratt on God’s absolute perfection. Yet underlying their exchange is the more general conflict between one BYU professor’s desire to engage in and expand discussion and one authority figure’s opposition to open-ended exploration and its potential to damage the kind of faith he felt was necessary to have for salvation. Both desires emerged from these men’s concern for others and, hence, deserve being honored in that spirit.

In 2001, seven weeks before his brain cancer was finally diagnosed and when he was struggling with severe anxiety, depression, and physical discomfort, England wrote a journal entry he titled “The Voices I Hear.” He included as eighteenth in a list of nineteen voices—those of family members, friends, university administrators, and Church leaders—Elder Bruce R. McConkie, along with a line paraphrasing the famous one in the 1981 letter: “My job is to define doctrine. Your job is either to support what I say or be quiet.” During this period of depression and anxiety that was so uncharacteristic of him, England occasionally wondered if he was experiencing the effects of unresolved anger about his forced retirement from BYU in 1998, and he also privately commented to a few close friends his utter bewilderment at the poor treatment he had received from some apostles, whom he continued to sustain as inspired servants of God. Following the diagnosis of his brain cancer and removal of the malignant tumors, though he was dramatically limited physically and mentally, England regained his characteristic optimism and faced his death unburdened by past regrets and unreservedly expressing his core beliefs and love to friends and family.

_____________________

Human beings cannot be reduced to an action, a political or intellectual position, a quotation in a newspaper, an essay or a story they have written…. We are never less—and actually much more because of our infinite potential—than the complete sum of our history, our stories, a sum which is constantly increasing, changing, through time.

—Eugene England, “On Spectral Evidence,” 1993

NOTES

1 Claudia L. Bushman, Contemporary Mormonism: Latter-day Saints in Modern America (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006), 149.

2 Charlotte England, conversation with Kathleen Petty, circa May 2009.

3 “The Only Living and True God,” transcript of remarks by Joseph McConkie at Flea Market, September 1979, in Eugene England Papers, Special Collections, University of Utah Marriott Library.

4 Bruce R. McConkie, “The Seven Deadly Heresies,” in Brigham Young University Speeches of the Year (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1980), 74-80. Copy of original, unrevised transcript in Eugene England Papers.

5 Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City:Deseret Book, 2005), 101

6 Prince, Gregory A. and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2005), 49–53.

7 Eugene England quoting from Boyd K. Packer, “’I Say unto You, Be One’,” in Brigham Young University 1990–1991 Devotional and Fireside Speeches (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1991), 84.

8 Gary James Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum: Orson Pratt, Brigham Young, Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002).

____________

Links to the Letters

The following items are the intellectual property of the Eugene England Foundation. The foundation expects website users to follow carefully Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials guidelines.

Eugene England to Elder Bruce R. McConkie, 1 September 1980. This is the letter that initiated their exchanges over the issue of Mormon doctrine concerning whether God could both be perfect and progressing.

Elder Bruce R. McConkie to Eugene England, 19 February 1981.

Additional items related to this topic and its aftermath can be found in the Special Collections page of this website.

A valuable summary on a key teaching about God. It not only concerns the nature of God, but our own post-mortal destiny.

Thanks, so much, Wayne!

Alerting here that we just posted additional England and McConkie correspondence in the Special Collections section, and we will continue to build up more releases there. Hope you will find some things helpful for your interests.

I am so grateful for this summary of what ocurred between Brother England and Elder McConkie. Eugene England’s nature causes me to weep as I find his example to be one I wish to follow. He knew the Savior and taught the true nature of God better then anyone I know. Thank you Rebecca for this gracious account.

Beautiful comment, Kandee.

This was an excellent write-up. Thanks!

Thanks for the great overview of the exchange between Eugene and Bruce. Eugene’s humble and meek response to correction (whether justified or not) is an example we should study in our Gospel Doctrine classes. How difficult it must have been for Eugene!

Lesson: a Prophet does not know everything but deserves to be listened to and his council should be followed when he is acting in that office. All of us have an understanding of everything and our understandings change as we progress. Our differing and changing understandings are not going to damn us but our failure to follow the Prophet will. This does not mean we have to have the same understandings (beliefs) about everything as the Prophet but to be saved we must accept and worship Jesus Christ. It does not matter whether we believe him to have blonde or brown hair, it does not matter if we have a perfect understanding of who He or his Father is.

Well-said! At once heart-wrenching yet soul-strengthening.

England should have ignored McConkie. McConkie was acting outside of the bounds of his authority. The Twelve have never had the authority to decide the doctrine. That belongs to the First Presidency.

I appreciated Eugene England’s letters to me he wrote many years ago when i was in the LDS church. He sounded like a good man. I found the same in letter exchanges with Lowell Bennion. Funny how the people who raise questions are that ones that get attacked. Joseph Fielding Smith attempted to get Bennion exed however David O Mackay stopped it.

My mind is at rest now since I am more of an England type thinker. The portrayal of Professor England in this post makes me want to be more like him. Thank you for sharing these insights about the two men.

[…] McConkie’s Son “Rebukes” Eugene England […]

Call me crazy, but I don’t think it is the prerogative of the twelve or the first presidency to determine doctrine. Christ explained his doctrine, which was to have no contentions, to repent, and to be baptized. In matters of belief even, I don’t believe that anyone is authorized to reduce the gospel into a system of dogmas, creeds, and “doctrines.” That is completely contrary to the teaching of Joseph Smith and to the standard works. The Lord encourages us each to ASK questions, whereas we have become a people wholly satisfied with simply having the “right” answers. Not to mention that we get our “right” answers from other men and don’t struggle through the process of receiving them through the vehicle of revelation itself. It’s really easy to believe and have faith in concepts that you yourself have created. It’s much harder to figure out the mind of God. I think this letter is an embodiment of why people call our religion a cult. We have created a sort of priority that defers in all ways to the leaders of the church who, according to McConkie, don’t actually have all the answers. This sounds very much to me like giving deference and maintaining power and influence by virtue of the priesthood or by virtue of a calling in an office. This is expressly forbidden in D&C 121. We really must experience a cultural shift in LDS culture or we are doomed to a sort of self-imposed religious tyranny as soon as someone figures out that he can control 13 million people by working his way into an upper echelon of church leadership. Brigham Young was terrified by this prospect. George Q. Cannon was terrified by this prospect. Joseph Smith was terrified by this prospect. Follow Christ. Love God. Love your neighbor. Take the Holy Ghost as your guide. Have mercy. Forgive.

The beauty in this account is its affirmation and reminder of the essential message of Professor England’s seminal “Why the Church Is As True As the Gospel” essay. Professor England summarized that message himself, teaching that, “the Church is not a place to go for comfort, to get our own prejudices validated, but a place to comfort others, even to be afflicted by them.” In this episode of his life, we see a perfect example of this process at work. He taught us that the Church “is a place where we have many chances to repent and forgive—if, for a change, we can focus on our own failings and the needs of others to grow through their and our imperfect efforts.” From this account, we learn of his efforts, perhaps imperfect but nonetheless sincere, to focus on his own failings, to repeatedly repent and forgive, and to act out of love for the Lord and his students. There is much we can learn from his example. Clearly, Rebecca, you captured the essential lesson for all of us: deciding who was right and who was wrong is impossible and irrelevant. What matters is that both were sincere believers seeking to develop and express their testimonies of the nature of God. If we can somehow learn to disagree with people without attacking their sincerity, intelligence or integrity, the world will be a far better place.

Thanks for your comment. Especially about the nature of attending church.

(Moroni 10:4,5) already tells us how we can know “the truth of all things”!

(Moroni 7:46,47) tells us that “all things must fail-” but charity “endureth forever”. Charity never “faileth” Why rely on the arm of flesh? (England or McConkie) when the Lord has already made bare His Holy Arm? In the end it doesn’t really matter who knows what is right. Satan knows what is right but he doesn’t have charity because he has no faith, no hope, and is not meek and lowly of heart. (Moroni 7:45) “And charity suffereth long, and is kind, and envieth not, and is not puffed up, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil, and rejoiceth not in iniquity but rejoiceth in the truth, beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things.” “if ye have not charity, ye are nothing”!

Great to read both sides of the story. Why is a learned professor sending a letter to an apostle of the Lord to debate with him, he knew his stands on the issue. In his response he gives the old college try to humbly follow his direction but after McConkie’s death brings it up again. He hadn’t truly dropped the issue. Did he desire the power and respect that an apostle receives? Deep down was he jealous and wish he was called and given a position importance and power?

I have no interest in being like England; I am interested in learning and growing. If he had questions regarding progression didn’t he needed to seek personal revelation on the matter which we all have the right to. I doubt he was inspired to write a letter a member of the 12 and share some of his “ideas” to help further the education of an apostle, or that the spirit whispered to him to teach this doctrine at BYU. Sounds like he wanted to be the man on campus that was known as the profound thinker. We all want to be loved and feel important but pride, ego, ect can be dangerous. I really don’t want to dog Brother England but that’s what I felt when I read the above. Obedience can be a tuff one. Perhaps that’s why charity and humility are the last pieces of the perfection puzzle that fall into place for most of us, well at least it is for me.

But then what do I know, I’m just an old, bald fat guy trying to be a better person. Thanks for every ones thoughts, they all seemed sincere and respectful.

You state “I have no interest in being like England; I am interested in learning and growing.”

It seems obvious to most readers that it was Elder McConchie who was the prideful one, having received several rebukes from the First Presidency, and Prof. England who humbly sought the advice from his ecclesiastical superiors. To judge Prof. England as “jealous” is totally unwarranted from anything anyone who knew him wrote or spoke about him. You have no evidence on which to base your opinion it seems to me.

The presumed “rebukes” from the first presidency are just that, presumed. No one has presented anything that shows the nature of these presumed rebukes (if they occurred at all).

It is McConkie by the way.

Considering the historically ephemeral nature of many of the LDS doctrines (for example, the “Doctrine” or “Lectures on Faith” states that God the Father is a spirit, that only Jesus is corporeal), it seems foolish for anyone, even an apostle to cast doctrine in concrete of their own making.

One must wonder considering his own personal history of rebukes from the First Presidency if McConchie had a serious flaw of pride with which he struggled. It is an unflattering observation that he took upon himself more authority to speak in the Lord’s name than what was given to him. One would think this and his tendency to publicly humiliate people would be far more severe in the Lord’s eyes than the humble inquiry of a loyal member such as Eugene England.

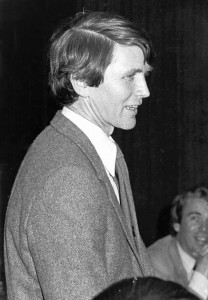

Winny, above, writes, “Great to read both sides of the story.” A surprising perception, I think. It’s clear to me that this article is a Mormon liberal diatribe criticizing a dead LDS apostle. Even visually, on the face of it, look at the earnest photo of England, and then the frantic-faced photo chosen to illustrate Elder McConkie – (oh, excuse me .. “Bruce”).

And, “The historically ephemeral nature of LDS doctrines,” Mr. Lowther? Read the statement in the “Lectures” again; you missed something. Mormon liberals often do.

Dear Glen: I tried my best to be objective in explaining the decades-old interaction between two devout Latter-day Saints and providing context to an infamous letter by McConkie addressed to my father. In fairness, I quoted or paraphrased praise for and criticism of both individuals involved. Of course I love my father, but I tried also to be sympathetic to Elder McConkie, as I saw my father be when I discussed the controversy with him. I’m sorry you didn’t care for the choice of photographs. I couldn’t find another photo of Elder McConkie at the pulpit from that time period. I quite like it, since it reveals the earnestness and passion I remembered in Elder McConkie’s body language when he preached at BYU during the early 1980s.

I just bought the book about your father. Never heard about him before today. Then got excited to learn more and googled him where I fell into this controversy with McConkie. It’s like a movie where the two main characters have to face each other in a final dual. A duel to the death. Where the death of one frees up the other one to have his final say. Your father could not have faced anyone else in the church who could have been a worthy opponent. And sadly, elder McConkie character doesn’t end well. He lost. I wish I could have known your father.

Dear Glen,

Read Elder McConkie’s letter again and see if you can find any examples of his humility, openness, recognition of his own human fallibility, capacity for committing even the slightest of errors, compassion, or gentleness. Compare Elder McConkie’s letter and Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. I think you missed something.

One more comment:

If David O. McKay truly ordered the publication of Elder McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine stopped, how is it that the book was published via Deseret Book throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s?

After a comprehensive review of the book by Elder Marion G Romney, the First Presidency issued an instruction in January 1960 that the book was not to be republished.

Elder Mark E Petersen had also given an oral report to President McKay in which he recommended 1067 corrections to the book.

In 1966, Elder McConkie approached President McKay and asked if the book could be republished. President McKay, who was 92 years old and in failing health, did not consult the other Brethren but agreed that the book could be reprinted but only with extensive editing and revision which was to be done under the mentorship of Elder Spencer W Kimball.

Because it’s popularity encouraged President McKay, in mid-1960’s, to have Brother McConkie to re-edit the book with Elder (later President) Kimball. In 1972, He was made an Apostle and there was no way it was going out of print after that. It has, however, been out of print since 2010.

I have not been aware of the exchange between Eugene England and Bruce R. McConkie. After reading this latest content, the respect toward Eugene England increased. Thank you so much Rebecca England for posting this article. I see a somewhat similar conflict between an intellectual leader and an opposing, very consevative authority here, which is comparable to or continuation of, in my mind, B.H.Roberts – James E. Talmage vs. Joseph Fielding Smith conflicts generations ago.

I feel saddened when I comprehend the full extent of this episode. I already knew that Bruce R McConkie was an arrogant, unpleasant bully because W Cleon Skousen revealed this shortly before he died.

McConkie had been repeatedly censured by the President of the Church and his book ‘Mormon Doctrine’ had been severely criticized although it managed to live on in an edited form.

It is only the President of the Church, the Senior Apostle, who has the power and authority to reveal doctrine and declare the mind and will of the Lord. Of course, any revelation is subject to the sustaining vote of the other Brethren and the Church at large before it becomes ‘official doctrine’ or scripture. Hence why most of the polarising doctrines on the nature of God and the identity of God have not been formally accepted by a spiritual inept Church.

I sustain the men who are called to serve as special witnesses and pray that they do their best but Im also fully aware that they are human and therefore capable of arrogance, deception, bullying and the teaching false doctrine etc. They have good days and they have not so good days.

Like Brother England, I am inclined to believe the doctrinal teachings of the Founding Prophets of the Church, Joseph Smith and Brighsm Young, and not the teachings of those who wish to spend their time being in denial of what has been taught and who would rather teach their own particular version of Protestant theology.

May the memory of Eugene England as a kind, sensitive, considerate and truth loving man live on.

I was attending BYU at this time and I remember my astonishment at the McConkie letter as well as the admonishment of Professor Pace. I remember being very indignant and expressing myself at a party my disappointment at the tone of such a missive. There was an awkward silence after my tirade and someone then introduced me to Dr. England’s son, Mark, who was in the group of students that was listening to my complaints. Mark showed all the grace and composure that his father was famous for. As a result of the mutual friends, I spent a limited time with Mark and his family and remember well the ice cream parlor his mother opened. It was a revelation. I’ve never had ice cream that good, before or since and I think I tried in vain to single handedly keep it open. To this day, I hold Dr. England up as a model of how an original thinker should be and act. I still hold him up as an example when anyone tries to proffer that the LDS church is engaged in group think.

I wonder how the aggrieved parties felt when they came to the words, “The knowledge and power of God are expanding” whenever they sang “The Spirit Of God” in Sacrament Meeting. I’m sure this could be well-debated, too!

Hi brother Gallagher,

In the context of the hymn, “The Spirit of God” it become clearer, I think, when you read the second half of the same sentence: “the veil over the earth is beginning to burst.” It is, then, the knowledge of God “in the earth” that is expanding.

But what really troubles me is the veiled arrogance in the culture of Mormon liberals, including Eugene England’s. What is excused in this article is the fact that England gave his word that he would stop promulgating his pet doctrinal theory, and then later went back on his word (as soon as he could get away with it following Elder McConkie’s death). So much for honesty and integrity, and so emblematic of pseudo-discipleship.

George R. Gallagher: “I wonder how the aggrieved parties felt when they came to the words, ‘The knowledge and power of God are expanding’ whenever they sang ‘The Spirit Of God’ in Sacrament Meeting.”

Don’t forget the next line after the portion of the hymn that you quote: “The veil o’er THE EARTH [caps mine, for emphasis] is beginning to burst.” God’s knowledge and power are expanding, among humankind, as we come to know Him more and to exercise a greater portion of His Power.

Our hymns are typically poetic. Poetic style and format put severe restrictions on the ways that concepts, and even frank truths, can be expressed. Poetic rhythm puts tight restrictions on the number of words (or at least syllables) that must be placed in a line; end of phrase rhyming (especially in music) is commonly standard, if not actually required. Sometimes the antecedents of pronouns might be somewhat ambiguous (or at least unstated). The disputed line has more than one reasonable interpretation. “The knowledge and power of God are expanding” might mean that God is getting smarter but more reasonably probably means that the church, the saints, and/or the world is growing in its understanding of God, as in “The world’s knowledge of God is expanding,” or “The saints’ knowledge of God is expanding and increasing the power (influence) of the Gospel in the world.” Neither of these substitutions is poetic; both would spoil the rhythm (and thus the message) of the hymn. Whose knowledge is expanding could be understood various ways; the rhythm does not allow space to clarify the antecedent of “whose.” It is mistaken to accept poetic license as doctrinal in the same manner that we accept scripture and statements from the authorities.

[…] our tentative majors. I wasn’t aware back then, but this was a tumultuous time for Dr. England (http://www.eugeneengland.org/a-professor-and-apostle-correspond-eugene-england-and-bruce-r-mcconkie-…) and I more deeply appreciate his instruction and interest knowing now what was going on in his […]

I had the pleasure of taking a class from Professor England the semester or two before he passed. I have never met a man more devoted to and passionate for this church. His classes were spirit filled, his testimony was one of the firmest I have ever heard. It was so strong because he was willing to ask questions and test the foundations of faith. He emerged with a firm understanding and a deep devotion. This is a church founded upon asking questions and seeking answers, that is the nature of revelation, and revelation is the foundation of the Church. I know the how the spirit feels and Eugene England taught with it every class. I really miss him. I didn’t know at the time he was so sick. I wish I could have told him how much he meant to me. It is because of men like Nibley, and Maxwell, and Eugene England, that our faith is challenged and renewed. I am fortunate to have met all three. They have taught me tolerance for ignorance, and passion for research, and devotion to truth. I don’t know if the family of Professor England reads this, but if you do, thank you so much for sharing him with us. He has changed my life.

Thank you for what reads like a fairly objective treatment of what happened. Though many of the comments here take a side, I do not. I’m not hiding what my side is, I really don’t have one. What I see is the weaknesses of two men, and one is an Apostle. Both were overzealous in very different ways. I don’t believe theory and intellectualism is a fountain for revelation, too much like make believe for sophisticated adults. I also can see how Elder McConkie went above and beyond the call of duty time and again to enforce the unenforceable. Such are the problems when we reach beyond reveled doctrine and our authority. That is what value I can offer to salvage whatever time you spent in what appears to be a total diversion from fundamental saving truth. May each man be remember for something of far greater value than this display of faults.

Ugh. I came across this thread after getting all worked up about John Dehlin – new wounds that have been gouged deeper and that are probably not going to heal without leaving scars.

I already regret the way a made some replies while in this state of angst, mainly because I was ill informed at the time, but then again, my thoughts tend to go much further at times like these

So far, this thread has presented more of the kind information needed to set my soul at rest than any other I have encountered.

I in no way want to try to equate the character of professor England with that of Mr. Dehlin but I see a recurring pattern in how sides are taken and I do think that the spirit of Professor England could spill over and promote some healing in the current controversy. The current case having me on the so called conservative side and what is being discussed here pulling me on the so-called liberal side.

The quality of the comments here is uplifting to me. I hope I don’t contaminate it with the with current baggage I am bringing with me.

So first a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche

It is not when truth is dirty, but when it is shallow, that the lover of knowledge is reluctant to step into its waters.

OK, so at the the risk of dirtying things up a bit. here is my attempt to add some depth.

I believe that this is the Lords church and that he directs it to his ends, one of which is to pour down knowledge upon the heads of latter day saints.

For me, The spirit of Elder McConkie’s letter violates the part of the sermon on the mount which says “seek and ye shall find”.

I seem to observe that the “witness of the Savior to the world”. fails to mentions that aspect of his calling at all in the letter. He doesn’t seem to be calling anyone to “come to Christ”.

Facetiously put, Professor England seems clearly to have been meekly asking for some fish and received a rather copious serving of a serpent flesh instead.

So the question I want to entertain here is this: “Did God make a mistake when he called Bruce R. McConkie to be an apostle or not?”

Despite the reservations Spencer W. Kimball must have had about Elder McConkie, he called him to work on the new edition of the standard works and many of the chapter heading seem to have a certain flavor to the that reminds me of Elder McConkie. For instance. when Paul gives his advice about not getting married, all doubts are quickly laid to rest when we are informed in the heading that this advice is for Elders who are going on missions. Now who would say a thing like that?

I am inviting people who are troubled at length by this kind of controversy over whether one gains knowledge by study and by faith or by appeal to authority, – to spend some time studying Alfred Adler’s concepts of what he calls “fictional finalism” as it pertains to what he calls “teleology”

Much of the work we do in the church is not so much different in nature than much of the work we do in the world. (For instance, as I was growing up, the son of a protestant minister we used to think that at least half of the returned LDS missionaries had jobs as insurance salesmen)

To work effectively we need goals and to have goals we need constructs of truth – as it says in D&C 93 “all truth is independent in that sphere which God has placed it to act for itself as is all intelligence… otherwise there is no existence.”

I like to make a connection between the word intelligence, and the word teleology and even the word telestial which defines the kind of world we live in now where the Holy Ghost ultimately is our source of truth.

For instance. when Joseph Smith was asked what made his church different from all the rest, rather than mentioning apostles and prophets he simply said. “we have the Holy Ghost”.

President Henry B. Eyring made a tearful and impassioned plea for the attention to the importance this principle in just this last conference.

Summing up a bit: if the difference between what Adler would call the ” teleological (purposeful, goal defined)” endeavours carried our church and those carried out in others is that “we have the Holy Ghost” Why not take a second look at the sphere in which God place the considerable intelligence of Elder McConkie to act for itself. A sphere which according to some of the teachings of Brigham Young when Elder McConkie must changed once he stepped thought the veil and cried “Oh it’s you Adam!” (that not doctrine, just a hypothetical).

Well, I came across the letter in question on an anti Mormon site where he says

“Since then I have received violent reactions from Ogden Draut and other cultists”

When I google Ogden Draut I get Ogden Kraut and studying a bit further we may be able to gain some insight into what was actually going on in Bruce R. McConkie’s “sphere of action” at the time. I think he was genuinely concerned that if people started listening to Professor England they would end up listening to Ogden Kraut and more than a few of these would have become polygamists.

I regards to brother Pace, I seem to recall around 1985, a priesthood lesson in our manual which basically taught that we don’t worship Christ.

The fundamental point of logic presented there was none other than that of Elder Bruce R. McConkie where he quoted from D&C regarding the commandment given to Adam and Eve regarding the “only being whom they should worship”.(there may be something to think about there in regards to Michael a Co Creator.)

I remember thinking at the time “yea, but that was before the fall”

The next conference I heard Gordon B. Hinkley say “I worship Him, as I worship the Father” And then, when one reads to words in the hymn “I believe I Christ” one gets the feeling that some one, or some thing, definitely got thought to Elder McConkie by showing him the following.

2 Nephi 25:29 And now behold, I say unto you that the right way is to

believe in Christ, and deny him not; and Christ is the Holy One

of Israel; wherefore ye must bow down before him, and worship him

with all your might, mind, and strength, and your whole soul; and

if ye do this ye shall in nowise be cast out.

I think what happened is here is that he probably overstepped himself when he came to put an end to people following Brother Pace’s suggestion to go out in the wilderness and have an Enos like experience talking with Jesus. (for me, that’s here-say which I tend to believe)

Well, that was a bit of a digression but I want to say that the sphere which God placed Bruce R. McConkie to act for himself, he accomplished a great deal. I think that many of his logical constructs were obtained from extended conversations with his father in law who became the Prophet of the church and that he felt a unique obligation to organise many of those constructs and pass them on.

When one remembers that there were no personal computers to facilitate research in the days when “Mormon Doctrine” was originally written, and that the feelings of responsibility he felt must have been tremendous, it causes me to reflect on how servants in the kingdom who also didn’t have access to computers to do their research, were able to use the “fictional finalisms” of “the stick of Bruce” (as some of us used to refer to it), greatly augment the effectiveness of their “teleological” pursuits within the church to the eternal benefit of many other.

But may we never forget that, however loyal we are to liberalism or conservatism. That if we lose the Holy Ghost as we go about our individual tasks, we essentially loose it all.

I think that both of these great men were ultimately true to the principle of continual revelation in their own spheres of action and if we can do the same we can be greatly benefited by the great legacy left by both.

And I secretly wish that more latter day saints could study Alfred Adler’s paradigm of effective “fiction” As Paul Say “We know in part. we prophecy in part”, and as a result of thoughtful study of this principle, the amount of acrimony may be reduced on threads such as this so that the Holy Ghost may be enabled to touch the hearts of sincere investigators as the browse through threads like this one which has so very very much to offer.

Rick, thank you for your thoughts. You worried you were going to bring a negative idea to the discussion. From my perspective you provided a thoughtful, insightful and uplifting observation.

Elder McConkie’s implied claim that only Apostles can “teach doctrine” certainly doesn’t square with Joseph Smith’s views. In History of the Church 5:340, we find a fascinating story.

In April 1843, an elderly member, Pelatiah Brown, was “hauled up for trial before the High Council” because he had been teaching doctrine that some of Joseph’s more zealous associates considered heresy. Joseph remarked, “I did not like the old man being called up for erring in doctrine. It looks too much like the Methodist, and not like the Latter-day Saints. Methodists have creeds which a man must believe or be asked out of their church. I want the liberty of thinking and believing as I please. It feels so good not to be trammeled. It does not prove that a man is not a good man because he errs in doctrine.”

Joseph even admitted to laughing at some of Brother Brown’s ideas, but he defended the good man’s right to teach nonsense, even in the Church. I sometimes get the feeling that Joseph Smith would not feel very comfortable in today’s church. The hardliners would probably run him out of town for preaching things that contradicted other things he had said.

Late to the party, but very appreciative of Rebecca’s write up and many of the comments.

Curious about one comment asserting that President McKay has “agreed that the book [“Mormon Doctrine”] could be reprinted but only with extensive editing and revision which was to be done under the mentorship of Elder Spencer W Kimball.” I have seen a reference to Elder Kimball’s assistance with that editing in Joseph Fielding McConkie’s book on his father. Prior to coming across that reference I had never heard that SWK had anything to do with it. There is no reference to any such assistance (or assigned mentorship) in Greg Prince’s and WR Wright’s “David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism” or in Ed Kimball’s books on his father. I asked each of Greg and Ed whether they had ever come across any evidence of SWK’s involvement. Neither had ever heard anything about any such involvement of SWK in editing, revision, or republishing of Elder McConkie’s book. Ed did remark that there could be something in his father’s voluminous papers at the University of Utah that Ed was unaware of. I have been hesitant to trouble those few members of the McConkie family that I know about this, but I do wonder if anyone has any documentary evidence of SWK’s involvement, if any, with Elder McConkie’s book.

[…] I have already blogged about the amazing content of the letter which is so important for people to be familiar with as they try to work their way through the Mormon Maze, so I will not beat that dead horse again, however the circumstance behind the exchange between Apostle McConkie and brother England is really quite a fascinating and important story as related by the daughter of Eugene England. […]

[…] Mormon Pharisees are the same. Bruce R. McConkie wrote in a letter to professor Eugene England, “It is my province to teach to the Church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo […]

Rebecca,

Thank you for taking the time to write this article. I had a class from your father while I was attending the University of Utah in 1993-ish. He spoke to me personally about following the brethren, not a brother. His council has blessed my life. More importantly his character blessed my life. I look up to and admire your father in so many ways.

Excellent article!

Thank you for your kind words.

[…] [1] See Rebecca England, “A Professor and Apostle Correspond: Eugene England and Bruce R. McConkie on the Nature of God,” the Eugene England Foundation http://www.eugeneengland.org/a-professor-and-apostle-correspond-eugene-england-and-bruce-r-mcconkie-… […]

[…] Father.” The approach the Church takes is very much like the point Bruce R. McConkie famously made to Eugene England about Church doctrine: “It is your province to echo what I say or to remain […]

Dear Rebecca,

Your narrative of this exchange was truly moving. I think it shows how the struggle to remain true to oneself while working within a believing framework can be both frustrating and fruitful. And the institutional/individual concepts of authority/heresy, revelation/inspiration, and retrenchment/progression are illuminating. I’d like to do some further research on this as part of my masters, and so I am trying to locate Joseph McConkie’s “The Only Living and True God.” The wonderful librarians at the U’s Special Collections have been unable to find it for me. Do you have any ideas of where I might find it? I would love to talk more about this! -Shannon

Could I get a reference for Joseph McConkie’s “The Only Living and True God?” (footnote 3) The librarians and I cannot find it in the special collections archive. Thank you!

I went to St. Olaf College in 1974. Gene England picked me up at the MSP airport and took me to his farm home in Northfield (with a duck pond and a rope swing) to eat with his family and spend the night, and then delivered me to the dorms the next day. He was my branch president. When I learned, years ago, of his rather unpleasant experiences with Elder McConkie and BYU, I was indignant – I thought, “How can they do this to one of the best pastors in the Church and Kingdom?” I love this man who midwifed my being born again, and who helped me shed some of my childish ways during that freshman year, on my way to a church mission and manhood in the priesthood.

I echo all the good things that have been said about Eugene England in this forum and in other places and publications. But I thought, in the spirit of this good man, I would share another story about his opposite in this ‘dialogue’ between the professor and the apostle. I hope it is not presumptuous to assert that I think Brother England would want this anecdote to be as well known as the one about ‘the letter,’ in the spirit of fairness at a minimum, and more importantly (and characteristically of Brother England), in the spirit of love and mercy and the graciousness we owe each other as Saints who hope for those same allowances when we are seen and known of Christ and each other.

This was told to me by the missionary himself: Elder McConkie was touring their mission and came to speak at a gathering of the elders and sisters of the mission in a chapel. This missionary sat in the back with his native companion who did not yet have a command of English. While Elder McConkie spoke, he whispered the translation into his companion’s ear.

At the end of the talk, Elder McConkie asked to meet with the missionary and the mission president. In his rather bombastic way, Elder McConkie asked the missionary if he was to a point where he could ignore the words of an apostle and, instead, spend the meeting time chatting to his companion? “Oh no, sir, I WAS listening, but my companion doesn’t speak English very well, so I was translating for him,” was the humble reply. “Elder, come here,” said the apostle – “I owe you a deep apology – I am sorry for my assumption. I hope you can forgive me.” This as he hugged the young elder who, of course, accepted the apology.

This story, in conjunction with that fervent testimony of Christ (“I shall not know then any more surely than I know now…”) which he gave shortly before his death, has helped me to be more charitable toward this particular special witness. While it was not often on public display, he was capable of self-criticism and humility. And while the messenger might have been hard to take, the message he bore most frequently and fervently is crucial to our salvation. With Brother England, I am willing to let Elder McConkie and his letter rest in peace, and go on in the cause.

Thank you, David, for your memories and kind words about my father. I have countless wonderful childhood memories of my family’s years in Northfield, especially of Spring Brook Farm, St. Olaf and Carleton campuses, and the small Faribault Branch. I heard my father speak highly of his leaders often. I like your humanizing story of Elder McConkie apologizing to the young elder. I’m sure my dad would also. Best to all Haglunds.

[…] than free thought and open scholarship. To see just one example of this, one can view the England-McConkie Correspondences which historian Claudia Bushman has described as “a microcosm of the diverging […]

I read Mr. McConkie’s letter to Mr. England and found nothing wrong with it. It is not the place of BYU to promote or introduce incorrect doctrines and principles. Bruce McConkie’s explanation of Brigham Young and Wilford Woodruff’s errors is absolutely adequate and doesn’t require any kind of reconciliation. They were not prophetic statements, they were errors of Brigham and Wilford, not of their office.

I’ve taken quotes from Joseph Smith and concluded that God the Father is a Christ and that we are actually the spirit children of the men whom Elohim redeemed, rather than Elohim’s direct offspring. And Christ will be the “Father” of the spirit children of the men whom Jesus redeemed. All from statements made by Joseph Smith. And it all works with its own internal logic.

I personally am not impressed by broad, far-reaching conclusions about the eternal progression of God based on a few erroneous statements made by fallible men on new and groundbreaking doctrines introduced in the restoration. No matter the consistency of their own internal logic.

There’s not much of a compelling reason to assume God is increasing in knowledge. And the Scriptures speak contrary to it. You also have to ask, what is it exactly he is progressing towards? What knowledge is he gaining that causes him to increase? Is he transforming into the transcendent essence of the Trinity? Has he burst through the veil of his own sphere and has begun climbing his way up the social ladder of a cliquey eternal Golf resort? Do we believe in the immaterial spirit world of the creeds now? Where do you progress beyond material?

Bruce McConkie is absolutely correct about sound doctrine and the type of faith required for salvation. When I would speculate and reach all kinds of far, broad reaching conclusions about the nature of God and so forth. I would lose the Spirit of the Lord, because the Lord had become an intellectual plaything which would change with every new quote and theory and wind of doctrine. I was so beholden to theory and speculation that I somehow found my faith challenged by the idea of “multiple mortal probations.”

There is no power in speculation and theory. There is power in sound doctrine derived from the Scriptures and the testimony of apostles and prophets. There is certainly no power in a student Deity, and cannot save his creatures, as Joseph Smith taught.

[…] Letter to BYU Professor Eugene England, January 1981“It is my province to teach to the Church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo what I say or to remain silent.” — Bruce McConkie […]

[…] And outside of official general authority statements, there’s the famous exchange between Eugene England and Bruce R. McConkie on the nature of eternal progress itself which relates to the assumptions which underpin this debate. That exchange can be read here. […]

To the family of Dr. Eugene England. I am a retired physician. I love people and spent my whole life serving them. Our paths did not cross at BYU as I came as Eugene was away doing other things and left to go to medical school about the time he came to BYU to teach. I do wish I had had him as a teacher.

Later in my life I began reading Dialogue and have loved reading the things I could find about him. Elder McConkie set me apart for my mission to Argentina and he gave me a stern look of rebuke when my fiancee came with my mother to my setting apart at the old Mission Home in Salt Lake City. Later, I served in a district with his son, Mark.

As I have read the things I could get a hold of by Dr. England I have been impressed by the broadness of his thought and the kindness of his life, maybe more so than any other scholar in the Church. I too am a fly fisherman and have always felt that each quiet moment on the river was a gift from God and a revelation of his goodness. I would have loved to have tagged behind him on a steam just once.

To his family, I wish them to know how much I love Eugene even though he is no longer here with us. I feel like he is a kindred friend and love him like no other author I have ever read.

Thank you for this website. May God Bless You.

William LeRoy

[…] McConkie vehemently opposed England’s speculation that God might be progressing, saying that the Almighty’s perfection is absolute, and in a letter wrote: “It is my province to teach to the church what the doctrine is. It is your province to echo what I… […]

[…] According to his daughter Rebecca, “most of England’s friends and family were unaware of his struggle to respond with integrity to McConkie’s letter of reprimand.” […]

Thank you for this beautiful website. I came to it from Terryl Givens’ recent biography of Eugene England, which quotes from it. I began the book on impulse, never having read much by England or having come across him despite studying English at BYU in the 70s. I was only vaguely aware of his reputation, despite benefitting from his great efforts by reading from issues of Dialogue. What an extraordinary man, and this monument shows what an extraordinary person he was lucky enough to find in a partner like Charlotte England. All this material opens my heart.

I remember hearing about the “McConkie letter” but never quite knew what it was, so I appreciated this background and context that sheds so much light on the complexities that people interested only in contention are not so much interested in. Though indefensible, the letter serves a valuable reminder of the corrupting influence of power and that everyone has their cringe-worthy moments, not merely we mortals. Now the incident is a fascinating and somewhat entertaining one that helps us understand a particular chapter of history.

All this makes me want to become a better and more useful person.

Thank you again, Charlotte England and Rebecca England.